As the coronavirus pandemic continues, its becoming clear that, for the foreseeable future at least, face masks are here to stay. Theyre mandatory on public transport, theyre compulsory in shops in Scotland, and from July 24, shoppers will need to wear them in England or face a £100 fine.

But as we all don our masks as evidence in favour of the garments effectiveness in curbing the spread of coronavirus mounts, obscuring part of our face is having a detrimental effect on how some of us communicate with each other.

On a recent trip to Tesco, a cashier asked Leeds-based fashion and lifestyle blogger Luke Christian, who is deaf, whether he wanted a bag or not. Christian explains that the cashier got annoyed because he hadnt heard what theyd said. If I cant hear or understand somebody without a face mask, then Ill attempt to lip read or ask them to repeat themselves, he says. When they have worn a face mask and Ive asked them to repeat themselves, they get annoyed and angry.

For the 12 million people in the UK who are deaf or have some form of hearing loss, opaque face masks obscure the visual cues and facial expressions that many of them rely on to communicate. Words which sound similar but have different meanings become very difficult to distinguish. This can lead to a breakdown in communication, says Ayla Ozmen, head of policy and research at Action on Hearing Loss. British Sign Language (BSL) also uses lip patterns and facial expressions to denote certain words.

But even if you dont have hearing loss, many things can be lost in translation if you cant see the other person talking. Research undertaken in the past has proven that we use different parts of our face to convey specific emotions, whether thats by choice or unintentional.

“With disgust or anger, for example, a lot of the information comes from the mouth region. It might be the tiniest twitch in the levator muscles, the muscles that draw the lip corners back and down, that might reflect my mental state,” says Bhismadev Chakrabarti, professor of neuroscience at the University of Reading. “But if you were just looking at my eyes, I might be looking straight at you and you might not be able to guess the emotion just looking at the eyes.”

Conveying smaller subtle signals could also be an issue if somebody is covering up the bottom two-thirds of their face, which could cause confusion. Rachael E Jack, professor of computational social cognition at the University of Glasgow, says that while a smile might reach the eyes, a contended expression of understanding or a pinch of the lips which reflects anxiety would most likely not. Research Jack conducted in 2009 has also shown that people in Eastern countries paid far greater attention to expressions in the eyes than people in Western countries, who pay more attention to the mouth to infer somebodys emotional state.

With that in mind, the maker community and firms are throwing up unique solutions to these communication problems which face masks currently pose. Back in June, game designer Tyler Glaiel created a face mask with a voice-activated panel that lights up when the wearer speaks, giving the impression of talking. While a click of the tongue will make the 16 LED lights form into a smile. Though Glaiel emphasised in the Medium post instructing people on how to make their own LED mask that the use of it is mainly for novelty reasons.

Japanese startup Donut Robotics has made a smart face mask which fits over your existing face mask, and can record conversations, make calls, transcribe them into text and translate Japanese into eight different languages. The company has raised over 28 million yen (£208,000) in funding on Japanese crowdfunding site Fundino.

More importantly, for communication purposes, the Donut Robotics mask can amplify the wearers voice which could help those understand what theyre saying through a mask. All face masks alter the frequency content of the speech signal, which means that every person in the UK will suffer from degraded communication, says Michael Stone, senior research fellow in audiology at the University of Manchester. You cut out the high frequencies, so the message that’s received at the listeners’ ear has lost those high frequencies.

The background noise, for example, still has the same frequency content, which hasn’t gone through a face mask, and that noise can disrupt your ability to understand the other person even further. I’ve noticed over lockdown, when people are wearing masks, it’s much, much harder to understand what they’re saying, adds Gwyneth Doherty-Sneddon, head of the School of Psychology at Newcastle University. If you’re somewhere where it’s particularly noisy, you will really focus on their lips while they’re speaking. That really significantly increases your ability to understand their speech.

But while the C-Mask and the homemade LED mask are interesting concepts, exemplifying how tech is disrupting mundane items, they might not be the best solution for resolving communication errors in everyday interactions. Its kind of a fun thing to do to be able to digitise your mouth, but really what we’re used to is seeing and hearing people as they are in real life, says Jack. As with many things, the most elegant solution might end up being the simplest.

A group of nine charities, led by the National Deaf Childrens Society, are currently campaigning for the use of see-through face masks. Something that could help, not just people with hearing loss, but help everyone understand those subtle communication messages which are lost when a portion of the face is concealed.

As a result, a number of companies are currently working on clear face masks and are crowdfunding on sites such as Indiegogo. Cliu, which is based in Italy, has made a face mask which has a transparent panel over the mouth area. The company has so far raised more than £58,000 in funding. Then theres the Leaf Mask, designed by Redcliffe Medical Devices in Michigan, which has so far raised a mind-boggling £2.7 million in crowdfunding, claiming to be the worlds first FDA-approved transparent face mask.

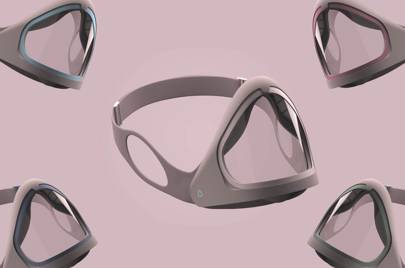

And besides letting people communicate more easily, the Leaf appears to be packed with a bunch of Covid-killing features. There are three variants to the Leaf Mask, which are the Leaf Hepa, Leaf UV and Leaf Pro. They all include an N99+ HEPA filter housed in the chin area and a permanent anti-fog coating on the inside of the mask. The UV and Pro models are built with a UVC light which the company claims can kill pathogens at the DNA level, and all of the variants are made of a soft silicone material.

The Leaf Pro adds two features to the mask. One is active ventilation. It has in-built fans. One fan creates an active airflow from outside to the inside of the mask, explains ASV, Leafs chief designer (yes, he insists on being called “ASV”). And it’s also got two sensors. One is a fully fledged air-quality sensor sensing humidity. The second one senses the dust level in the air. All of that data is sent to an iOS or Android app that ASV says is currently in development and will supposedly allow the wearer to monitor the airflow around them.

Because the material is thinner around the mouth area, at just 0.6mm thick, the audio crosses well, he explains. Any clear mask is fundamentally better than an opaque mask if humans are supposed to wear them for anything longer than a couple of months.

Ultimately, what these innovations highlight is how quickly humans can acclimatise to new ideas of normal. We are good at adapting, thinks Doherty-Sneddon. These different models and versions of face masks are an illustration of how humans adapt to whatever situation they’re thrown into.

Alex Lee is a writer for WIRED. He tweets from @1AlexL

More great stories from WIRED

☢️ Nine years on, Fukushimas mental health fallout lingers

🦆 Google got rich from your data. DuckDuckGo is fighting back

😷 Which face mask should you buy?